Taming the Torrens: From Floodplain to Outlet

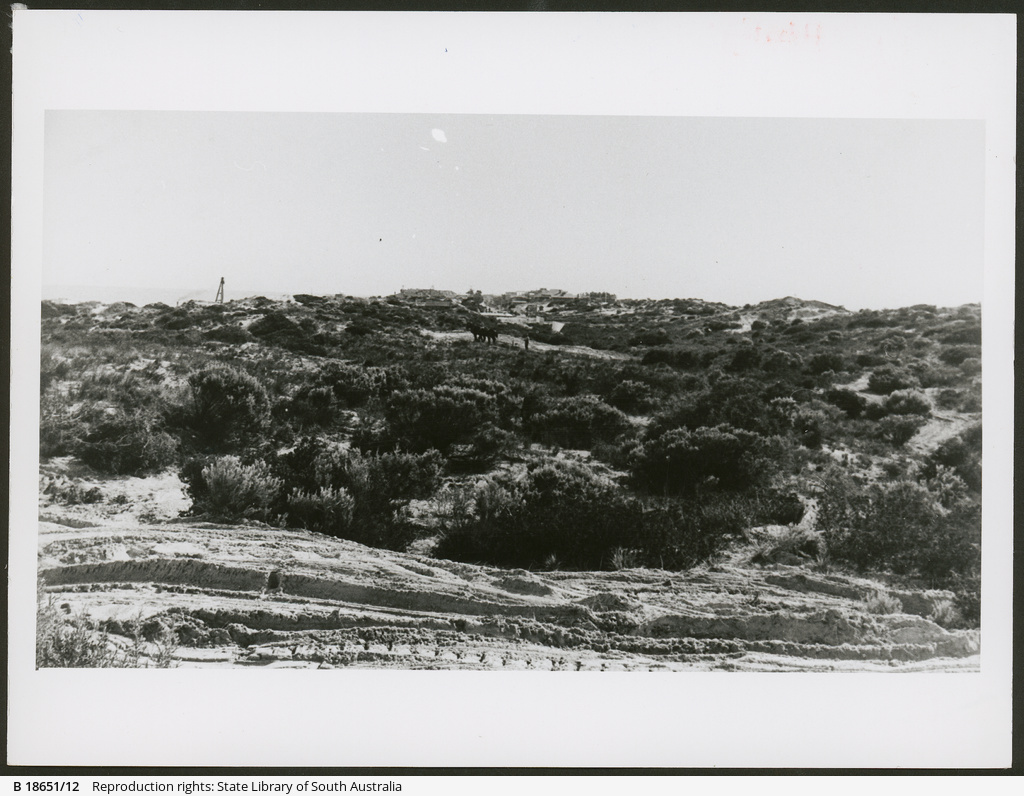

The Floodplain of Henley and Grange

For much of its history, Henley and Grange east of the sandhills was a natural floodplain. Water from the Adelaide Hills flowed down the Torrens River and, after heavy rain, fanned out across the low-lying land.

With only the narrow Breakout Creek as an outlet to the sea, the river regularly burst its banks. Vast floods swept across paddocks and backyards, leaving the district under water and cutting off local roads. For residents, flooding was not an occasional disaster but a recurring feature of life.

Living with Floods

Local memories capture the colour of these floods. In the 1983 Henley & Grange Historical Society Journal, Edna Dunning recalled racing home from school to rescue her family’s chickens before the water reached them. Like many households, the birds were placed on the back verandah until the danger passed.

She also remembered how floodwaters spread far and wide, carrying with them fruit, vegetables, firewood and debris, with locals flocking out to marvel at the torrents. These scenes were both destructive and strangely communal, part of a shared experience in the western suburbs.

Debating the Outlet

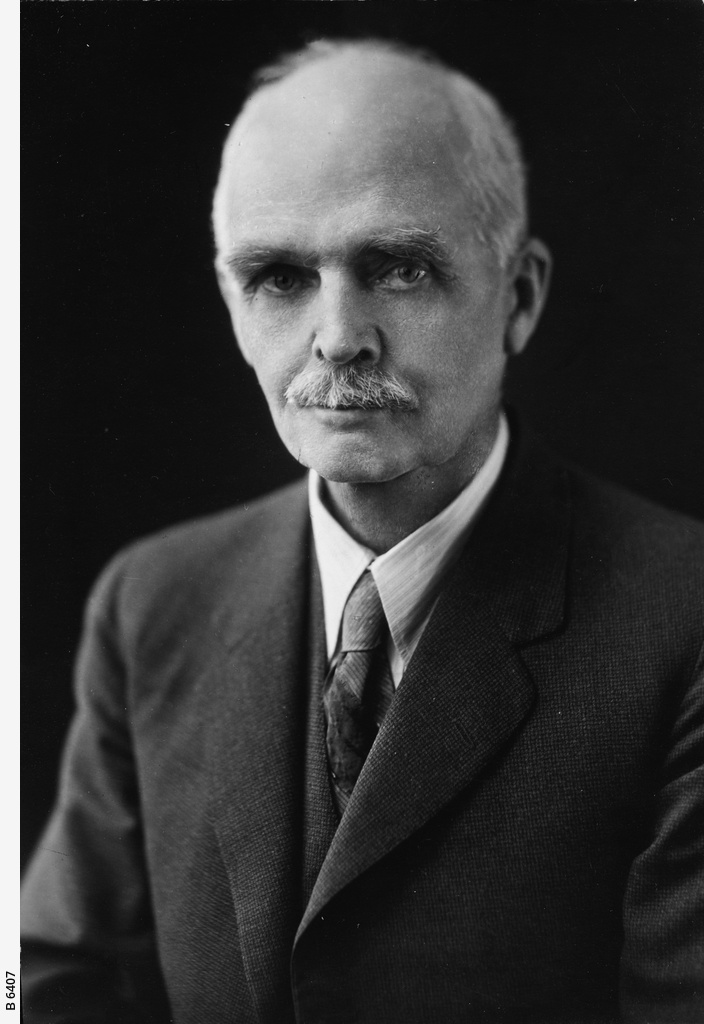

The regular flooding and its associated health risks — worsened by poor sewerage in the western suburbs — prompted the South Australian Parliament to act. In 1917 a bill was passed to mitigate the floods, but debate raged over the best solution. Some argued the waters should be diverted to their “natural” outlets: either north to the Port River or south to the Patawalonga. However, Chief Engineer J. H. O. Eaton recommended a direct cut through the Henley South sand dunes to create a permanent outlet to the sea.

This idea was fiercely opposed by local growers, represented by the “Torrens Floodwaters Vigilance Committee.” They feared the scheme would deprive them of water vital for market gardens and fruit orchards. Without agreement on costs or the route, the bill lapsed. A later 1923 proposal also failed, leaving the community vulnerable until two major floods in 1931 and 1933 forced the issue back into Parliament.

Engineering the Escape

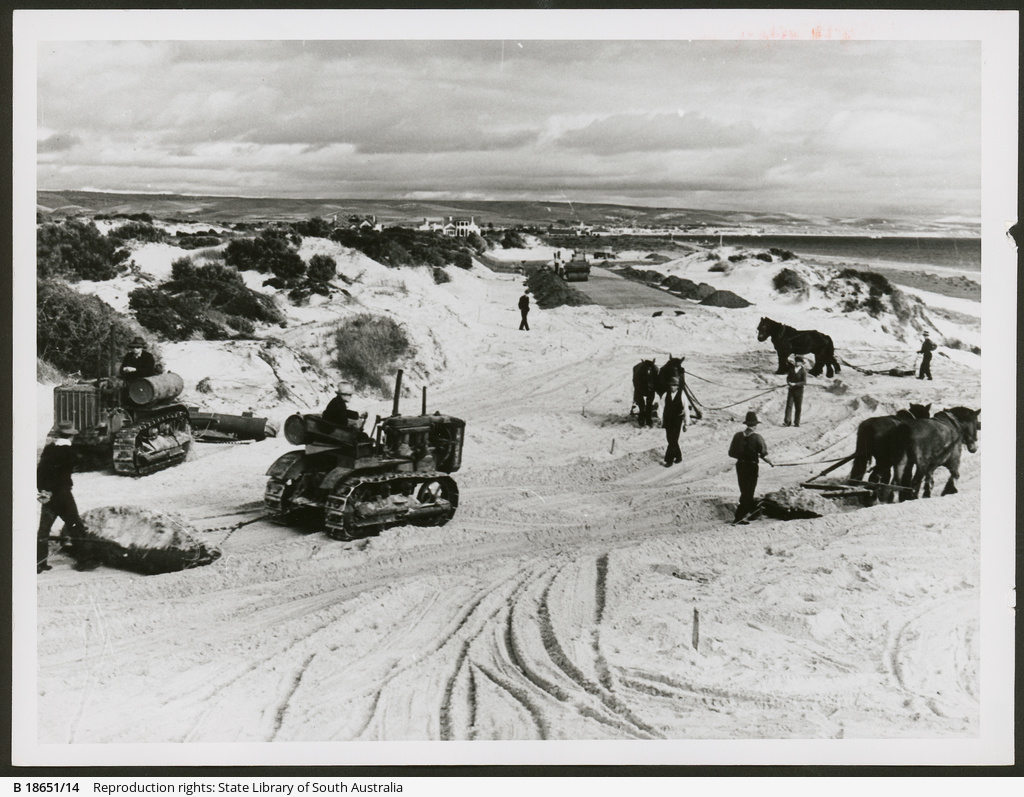

In 1934, Eaton’s original proposal was finally approved at an estimated cost of £360,000 (equivalent to more than $36 million today). The scheme diverted the Torrens at Lockleys, creating a new channel to the sea at Henley South. Construction between 1935 and 1937 was a major civil engineering project. Workers cut through sand dunes up to 12 metres high, removed over 76,500 cubic metres of sand, and built a reinforced concrete channel.

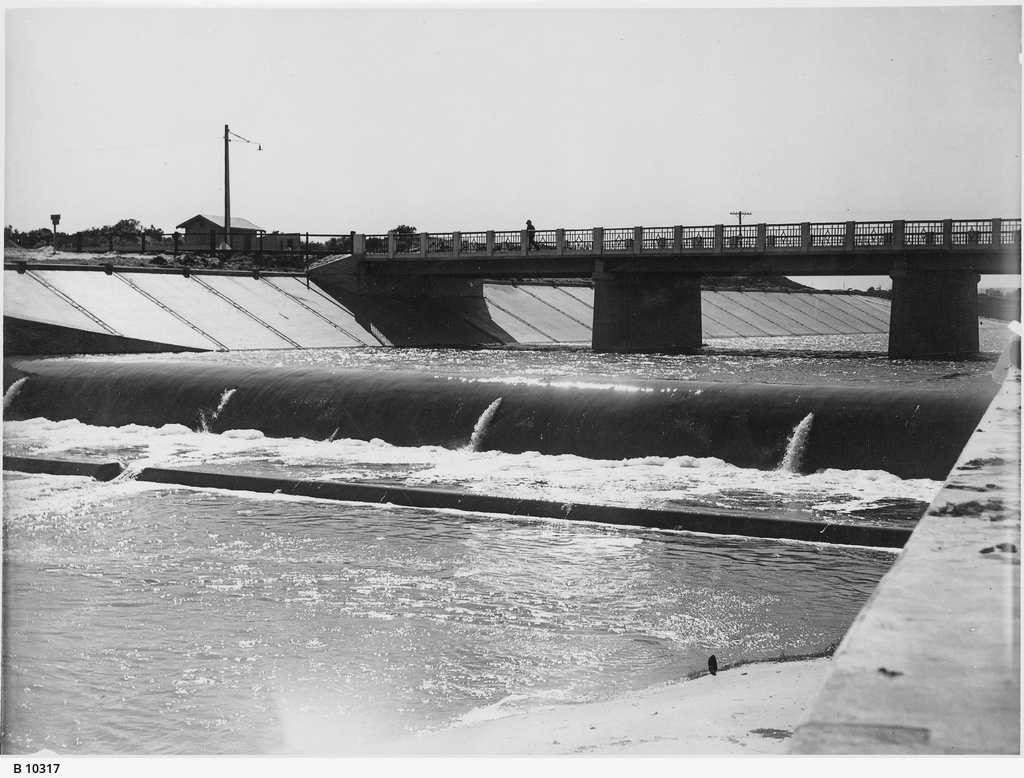

The scale was immense: more than 200,000 kilograms of steel piles, 878 timber piles, and 13 million kilograms of concrete were used. At the same time, Seaview Road was extended to West Beach, and a new bridge 45 metres long and 10 metres wide was constructed across the outlet. It was one of the largest local infrastructure projects of its era.

After the Outlet

Completed in 1937, the Torrens Outlet transformed the western suburbs. The age of widespread flooding was over. The wetlands, reeds and lagoons that had long defined the district gave way to new housing and suburban development. By the late 1940s, with the post-war housing boom and the spread of motor transport, Henley, Grange and their neighbouring districts began to grow rapidly. Small villages once separated by open paddocks merged into a connected suburban landscape.

The Torrens Outlet remains one of Adelaide’s most significant public works, marking the shift from a flood-prone plain to a thriving coastal community.